Background Structural Barriers to STEM Equity

Concentrated poverty is a policy-constructed condition under which economically marginalized families and students are clustered into under-resourced neighborhoods. This spatial segregation correlates strongly with race and ethnicity due to discriminatory housing practices, exclusionary zoning, and disinvestment in communities of color over time. This spatial segregation is deeply racialized and shapes both the environments in which children grow up and the educational opportunities available to them. As Milner (2013) argues, racialized poverty influences teacher expectations, school climate, and access to advanced learning. Schools serving high-poverty Black and Latino communities often interpret student potential through deficit-oriented frameworks that restrict entry into rigorous academic pathways, including STEM. Outside of the schoolhouse, concentrated poverty in the neighborhood affects child development through chronic stress and instability, exposure to environmental toxins, limited community resources, and frequent school disruptions. These aspects, among others, hinder cognitive functioning, learning continuity, and persistence in school (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

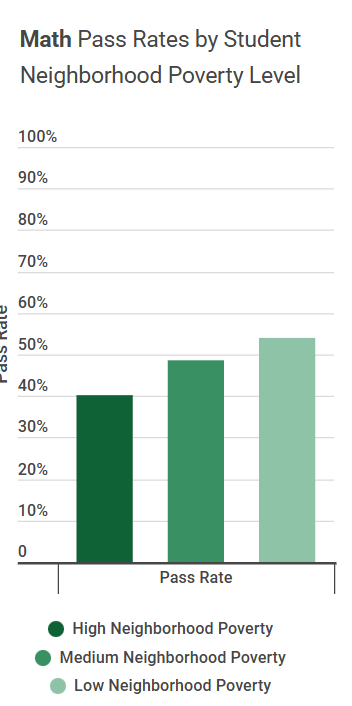

Figure 1. Math Regents pass rates by student neighborhood poverty level, New York City public schools. Source: New York City Independent Budget Office (2024)

According to Figure 1, math pass rates decline as neighborhood poverty increases, with students in high-poverty neighborhoods achieving substantially lower proficiency rates in Algebra 1 than their peers in lower poverty areas. This pattern suggests that academic outcomes are not simply a function of individual effort or school-level instruction, but are deeply conditioned by the broader environments in which students live. Unfortunately, these conditions reproduce themselves across generations, as Sharkey (2008) demonstrated that children raised in disadvantaged and segregated neighborhoods are likely to remain in similar contexts as adults. This finding suggests that spatial inequality is transmitted intergenerationally. When educational systems are nested within these inequitable neighborhood structures, they reinforce racialized disparities in wealth, opportunity, and social mobility across generations.

Evidence that the New York State Regents Math is a Structural Gatekeeper

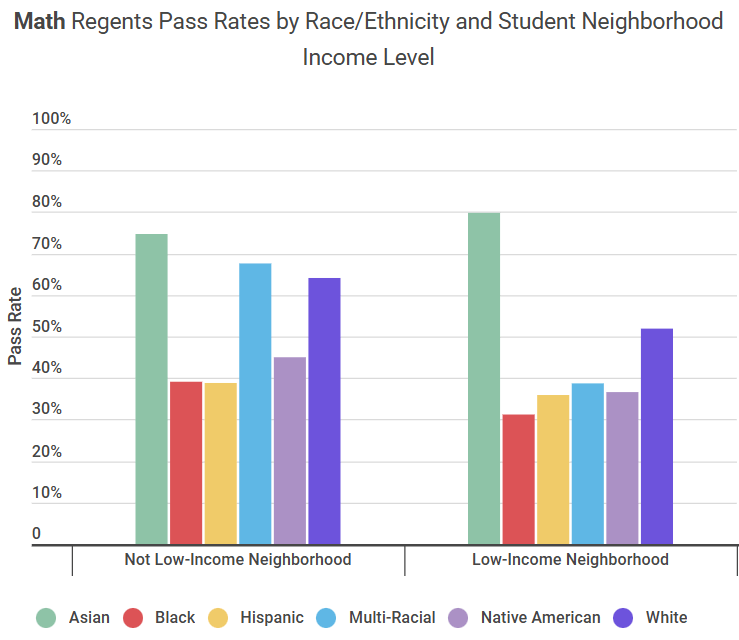

In the 2022–2023 school year, stark disparities in Algebra I Regents proficiency revealed how race and neighborhood poverty jointly structure access to STEM pathways in New York City. As shown in Figure 2, only 31% of Black public school students living in low-income neighborhoods achieved proficiency on the Algebra I Regents exam (IBO, 2024). While students in low-income neighborhoods consistently had lower pass rates than their peers in more affluent areas, the penalty of neighborhood poverty on test scores was not evenly distributed. While White and Asian students in low-income neighborhoods had pass rates of around 52% and 80%, respectively, Black and Latino students had pass rates of 31% and 36%, respectively. Figure 2 also illustrates that even when students share the same racial identity, neighborhood, there was a decrease in academic performance for each racial group except Asian students.

Figure 2. Algebra I Regents proficiency rates by race/ethnicity and neighborhood income level. Source: New York City Independent Budget Office (2024)

These disparities in academic performance among racial and socioeconomic lines reflect unequal access to preparatory coursework, experienced math teachers, stable learning environments, and cumulative academic supports, as these are resources that are systematically concentrated in higher-income neighborhoods. As a result, Regents math outcomes reproduced existing patterns of racial and economic stratification that have determined who is permitted to progress into advanced mathematics, science, and ultimately STEM career pathways.

If students fail Algebra 1, they are substantially less likely to take advanced math or science, including Advanced Placement courses for Calculus, Physics, and Chemistry. Reducing access to these courses is diminishing students’ access to STEM majors and careers as success in STEM requires years of practice and preparation. Due to previous years Regents scores, schools with low Algebra I pass rates may not offer advanced STEM courses at all, because low demonstrated proficiency reduces internal demand and teacher certification capacity. Therefore, Regents math outcomes have become structural filters that determine which students become competitive for college and STEM fields.

These school-level constraints, however, cannot be understood in isolation from the broader housing policies that shape school composition and resource distribution across New York City. Exclusionary zoning practices, including single-family zoning in suburban districts and neighborhoods such as Bayside/Little Neck, have restricted access to high-performing, STEM-rich schools by effectively pricing low-income families out of these areas. Meanwhile, communities such as Jamaica and Hollis remain economically and educationally marginalized, concentrating poverty and limiting access to schools with robust advanced coursework (Been et al., 2023). As a result, racialized housing policy operates as an upstream determinant of educational opportunity, sorting students into schools with vastly different capacities to offer advanced STEM instruction.

Limiting access to advanced math and science coursework undermines social mobility, especially for students from communities historically denied wealth-building opportunities, because STEM careers remain among the most reliable pathways into the middle class (Wilson, 2013). These inequities also widen the racial wealth gap, as the structural barriers produced by concentrated poverty and segregated schooling restrict the upward mobility of Black and Latino students. Over time, unequal access to STEM learning erodes public trust in the fairness and legitimacy of the education system and perpetuates intergenerational disadvantage (Sharkey, 2008). For these reasons, advancing STEM equity is both an educational priority and a core economic and civic responsibility essential to strengthening New York’s workforce, promoting social mobility, and sustaining a just and inclusive state economy.

Conclusion

STEM opportunity in New York is currently distributed based on residential sorting mechanisms rooted in racism and economic exclusion. Concentrated poverty ensures that children in some neighborhoods are never given the chance to become scientists, engineers, physicians, or programmers, which limits both their individual potential and the collective prosperity. To address injustice in the education system, the Legislature must treat housing policy as education policy, school funding as racial justice policy, and STEM access as an economic policy. The current financial and educational systems are disenfranchising our youth, and the resulting compounding problems require multifaceted, robust solutions. The Legislature must act now to ensure that every student, regardless of their race or place of birth, can have equal opportunities to succeed in our great state of New York.

Leave a comment